Freedom schools hold active intruder drill, students hold mixed opinions

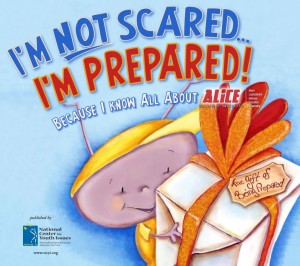

“I’m Not Scared… I’m Prepared!” by Julia Cook was a book that elementary students in kindergarten through second grade read to learn about an active intruder environment, as a suitable alternative to the active intruder drills at the middle school and high school for students in third through 12th grade.

It’s not uncommon to see a story on the news about a mass shooting. Throughout 2018, there have been 18 mass shooting — three of which have occurred in Pennsylvania. The FBI has defined a mass shooting as an incident where a shooter kills four or more individuals. This number doesn’t include the suspect if they died. Two of these mass shooting were at a school: Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida on Feb. 14 — 17 fatalities — and Santa Fe High School in Texas on May 18 — 10 fatalities.

As a precaution, the Freedom Area School District decided to hold an active intruder drill on Nov. 28, to prepare students in case of emergency. Third through 12th grade would go through a simulated active intruder drill, while kindergarten through second grade would be reading a book entitled “I’m not Scared… I’m Prepared” by Julia Cook.

The day before the event took place, all high school students gathered in the auditorium to discuss the events of the next day. It also gave students to ask questions to principal William Deal, if they had any regarding the drill. A mock active intruder would be going through the school to test the readiness for a potential active intruder situation. Deal instructed students to listen to whatever the teacher said and that fighting was not an option. Instead, the options were to either hide or run. Deal also mentioned during the assembly that while the drill was happening at the high school, the middle school would be doing a lock-and-teach, and vice versa.

The following day, the drill started at the end of first block. Over the announcements, the lockdown began, with the information that the intruder was on the second floor and that it was a drill. To assist with a situation where there was an actual intruder, everyone was to act as though an actual intruder existed. Though if that really happened was debatable.

“While the drill was taking place, students were laughing and not taking it seriously,” sophomore Gabrielle Barber said, “People were playing games on their phones and computers. The mood was chaotic, but it was like a normal school day.”

This was the same for many classes. If there was no risk in the drill, why should students care? More to the point, what would make the students realize the importance of the drill?

“After the drill had taken place, a few students and teachers had a discussion about what could have made the drill better and everyone’s answer was the same: the drill needed to be more realistic,” Barber said. “I believe that this situation is too serious for the students to be taking it as a joke.”

Though getting as realistic as possible would help students adapt to those circumstances, is there a limit to how stressful the experience can be for students? There is always the potential for a student to experience too much emotional stress. Is that a necessary risk for an event that might not happen?

On a separate note, one class at the high school didn’t quite complete the drill as planned. Ms. Catherine Schultz has a study hall first block and is in the balcony of the auditorium. When the office made the announcement, the plan was for Schultz’s class to go over to Ms. Heather Giamarria’s room across the hallway. However, when the class arrived there, no one let in the room. On top of that, the pretend active intruder was in that same area.

“The reason we were up in [the auditorium] in the first place is because we didn’t have enough room in my classroom,” Schultz said. “Kids have since moved out of the study hall for various reasons, so now we can have it in my room. The drill was definitely a factor in switching to my classroom. It was such an eye-opening experience to see that it was such an open target there.”

To signal the end of the drill, teachers received a green paper under their door. However, not every teacher received a slip. Instead, an announcement was made to let students and faculty know the drill was complete. This was not what the plan was, so some teachers made the decision to hold them until a text from Deal told them to release students to their next class.

The drill did give insight to students on what to do if an active intruder situation does occur, but the degree of insight varies from student to student. It is nearly impossible to replicate an active shooter drill, but to what costs should a district go to prepare its students for the worst?